Antoni Macierewicz: From Revolutionary to Government Minister

By Siobhan Doucette

Antoni Macierewicz, Poland’s defense minister, has quickly become one of the most prominent – and divisive – figures in the country’s new government, attracting international attention for overseeing the recent raid on a NATO facility in Warsaw and for alleged historical antisemitic comments. Through an exploration of Macierewicz’s progression from leading activist in the Polish democratic opposition during the communist period to government minister, our guest author, Siobhan Doucette, underlines the continuity of his thought and contextualizes many of his most controversial recent pronouncements and decisions, including his response to the Smolensk plane crash.

Poland’s new Minister of National Defense has been making waves since his appointment by Prime Minister Beata Szydło at the head of the Law and Justice (PiS) government, most recently for authorizing a raid on a NATO center in Warsaw and reopening the investigation into the plane crash which killed former President Lech Kaczyński. Controversy is nothing new for Macierewicz, who gained his political start in the Polish democratic opposition during the communist era and has, since the overthrow of communism in 1989, repeatedly been elected to the Sejm and served as Minister of Internal Affairs (1991-1992) and Chief of the Military Counterintelligence Service (2006-2007). An examination of Macierewicz’s political career indicates that many of the characteristics that made him a key player in the defeat of communism are the same that have made him such a divisive politician today.

Macierewicz first garnered political attention, like much of his generation, during the student protests of 1968. Then a student at Warsaw University, he was imprisoned from March to August 1968 and later suspended from university due to his participation in the protests. Despite the state-sponsored and popular antisemitism exhibited during and after the protests, Macierewicz, in the late 1970s, claimed that popular antisemitism was not a significant factor during the 1968 student protests. He also rejected the portrayal of them as leftist manifestations. Rather, Macierewicz insisted that for him and his milieu the motivating factors were Catholic beliefs and commitment to the struggle for independence and democracy. Macierewicz’s coterie, at that time, largely derived from Gromada Włóczęgów (The Gang of Vagabonds), a discussion group which had grown out of the Czarna Jedynka (The Black One) scout group, to which Macierewicz had belonged from 1966.

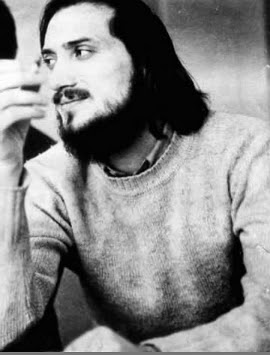

Young Macierewicz. [Source: Medialne fakty]

In June 1976, worker strikes and protests erupted across Poland. The state responded with repression and violence. Macierewicz, along with friends from Czarna Jedynka, supplied aid to the workers. With numerous intellectuals gathering to provide financial, medical, and legal support to the workers, in September 1976 the Committee for the Defense of Workers (KOR) was established. KOR is often associated with the political left and activists like Kuroń and Adam Michnik (who since 1989 has been editor of Gazeta Wyborcza, a left-liberal newspaper which has become an ardent opponent of the PiS party). However, it was Macierewicz who played the decisive role in the founding of KOR.

In September 1976, Macierewicz became the editor-in-chief of KOR’s Komunikat, which was Poland’s first mass-produced and long-lasting post-war independent periodical. Despite the opposition of certain members of KOR to the use of printing machines, Macierewicz, in late 1976, made the decision, on his own, to send KOR’s Komunikat to students in Lublin who had smuggled a printing machine into Poland. This decision was vital in allowing for the rapid spread of the KOR press and reflected Macierewicz’s goal to create a mass oppositional movement as well as his tendency to act as he saw fit even when it meant ignoring his colleagues.

Macierewicz was arrested with the rest of the KOR leadership in May 1977 and remained in prison until their amnesty in July 1977. After their release, KOR’s signatories voted to transform the committee into a broader organization for social self-defense. They also agreed to create new publications, including the socio-political periodical Głos, with Macierewicz named editor-in-chief.

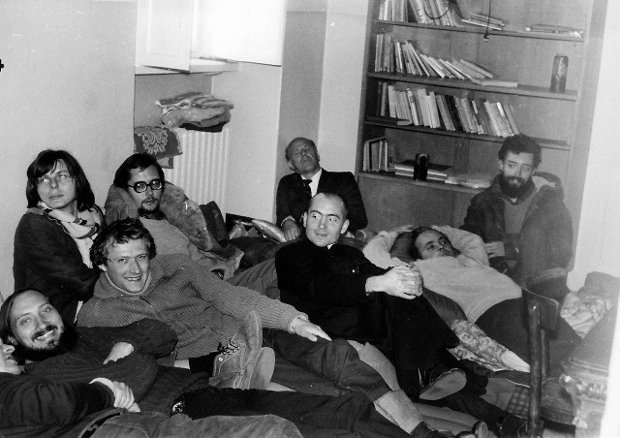

Macierewicz and Michnik in the foreground with other KOR activists (including Jacek Kuroń) at a hunger strike in 1979. [Source: Gazeta Wyborcza].

Macierewicz’s contributions to Głos foreshadow his contemporary foreign policy commitments. Most apparent is concern about, if not animosity toward, the Soviet Union, which Macierewicz described as a new manifestation of historic Russian imperialism. He insisted that Russia always sought to control Poland. Macierewicz also expressed anxiety toward Germany and raised the potential for the Soviet Union and Germany conspiring to take Poland’s “recovered lands” (the western territories taken from Germany and given to Poland after World War II). In addition, Macierewicz wrote of Poland’s betrayal at the 1945 Yalta Conference by the United States and United Kingdom and thus their untrustworthiness. Such arguments are pertinent in understanding Macierewicz’s skepticism toward NATO, the European Union, and Russia today. Macierewicz did, however, repeatedly support neighboring dissident movements, notably Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia. He also endorsed independence for Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania; denounced what he described as inter-war Poland’s imperialism toward these nations; and called for future cooperation with them.

Macierewicz’s writings in the 1970s also reveal much about his current domestic alliances and rivalries. Envisioning an active role for the Catholic Church in a future democratic Poland and endorsing the move toward a market-based economy, Macierewicz presented a tentative liberal-Catholic political identity. He also regularly voiced hostility toward the socialist left and those who had previously associated with the Polish Communist party. It is perhaps relevant that Macierewicz’s father died under circumstances which point to murder by the Polish secret police. Macierewicz suggested that many within the democratic opposition who identified as socialists were crypto-communists. While Macierewicz endorsed public protests due to his desire for a mass movement, Kuroń rejected them out of concern that they could be used as provocations. For Macierewicz, these apprehensions revealed a lack of trust in the Polish people and a failure to fully support independence by those on the political left. It is striking that while Macierewicz only hesitantly articulated his own political commitments at this time, he openly reproached his perceived political rivals, whom he portrayed as unpatriotic, if not treacherous.After the legalization of Solidarity in 1980, Macierewicz shifted his focus from KOR to union activism. He became chief of the Center for Social Research in Solidarity Mazowsze (based in Warsaw) and edited the daily Solidarity paper Wiadomości Dnia. Macierewicz’s differences with those in KOR’s left wing increased and were played out within the Solidarity press. Macierewicz’s virulent antagonism toward those with whom he disagreed led a faction from the “Głos group” to cease cooperation with Macierewicz. The divisions within KOR were conclusively exposed in the autumn of 1981, when KOR disbanded and Macierewicz joined the conservative Clubs in the Service of Independence, the signatories of which included future Prime Minister Jarosław Kaczyński and future President Bronisław Komorowski.

Tanks on the street after the imposition of martial law in December 1981. [Source: natemat.pl]

Macierewicz’s move, since 1989, from regime opponent to politician has resulted in an intensification of suspicions and antipathy toward perceived national and political adversaries. Macierewicz’s political Catholicism and nationalism have also become more pronounced. An opponent of Poland’s 1989 Round Table, Macierewicz has, with time, expressed heightened distrust toward those who were involved with it. As Minister of Internal Affairs from 1991 to 1992, Macierewicz was tasked with composing a list of those individuals in government who had, according to the files of the communist secret police, been informants. The release of this “Macierewicz list”, which included Lech Wałęsa, ultimately led to the collapse of the government of then Prime Minister Jan Olszewski (a former member of KOR’s “Głos group”). Macierewicz’s political star again rose in the wake of the 2005 elections, which resulted in Jarosław Kaczyński becoming prime minister and his twin brother Lech becoming president. From 2006 to 2007, Macierewicz served as Chief of the Military Counterintelligence Service. In that position, he disbanded the Military Information Service due to (debatable) allegations of ties to Russia and helped to create new intelligence services. Macierewicz was also Chairman of the Verification Commission, which investigated those charged with having been informants to the former communist secret services. After the fall of the Kaczyński government, Macierewicz remained in the Sejm and in 2010, became chairman of a PiS-sponsored parliamentary committee investigating the plane crash outside of Smolensk, which killed former President Lech Kaczyński. The committee controversially asserted that the crash was only possible due to an explosion on board the plane.

Since becoming Minister of National Defense in November 2015, following PiS’s landslide election victory, Macierewicz has become a lightning rod, both at home and abroad, for concerns about the right-wing leanings of the new PiS government. Almost immediately after his appointment, allegations of antisemitism arose. These were predicated upon a 2002 interview in which Macierewicz, when asked about the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, stated that, “experience shows that there are such groups in Jewish circles.” Macierewicz’s defenders, in response, pointed to his activism in 1968 as proof of his opposition to antisemitism. Macierewicz’s previous claims that his motivations in 1968 and popular responses to the student protests had nothing to do with antisemitism surely discount such defenses. However, one does not find any trace of antisemitism in Macierewicz’s extensive writings. Instead, this off-handed remark seems to reflect Macierewicz’s established belief in the possibility of conspiracy theories.Much more noteworthy are Macierewicz’s recent decisions and proclamations, which reflect longstanding commitments and beliefs. His insistence on December 14, 2015 that Ukraine is Poland’s “top priority” and his joint declaration of cooperation with the Ukrainian and Baltic Ministers of Defense mirror his claims in the 1970s and 1980s that Polish democracy and independence are tied to that of their eastern neighbors. Macierewicz will surely work to strengthen links with Poland’s eastern neighbors. These policies express not only goodwill toward Ukraine and the Baltic states, but also Macierewicz’s misgivings toward Russia; misgivings which are manifest in Macierewicz’s reopening of the inquiry into the Smolensk plane crash and assertion that, “the government headed by Putin is fully responsible for this tragedy.” The continued cooling of relations with Russia is a certainty for the new Polish government. Macierewicz’s authorization of a raid on a NATO center in Warsaw on December 18, 2015 points toward his skepticism toward NATO and the European Union as well as concern about foreign infiltration into the Polish security services. Finally, there is nothing to suggest that Macierewicz’s uncompromising animosity toward the political left is anything but unwavering.

Antoni Macierewicz had been politically active for almost fifty years. Over twenty-five years since the defeat of communism, Macierewicz’s political positions have remained remarkably consistent. His hostility, based in distrust, toward those on the Polish political left and Russia is resolute. Macierewicz’s reservations toward Germany and to a lesser extent the United States and the United Kingdom have also endured. At the same time, it is incorrect to suggest that Macierewicz is an isolationist. He has consistently endorsed and pursued close ties with Poland’s eastern and southern neighbors. Macierewicz’s repeated attempts at purging the government and military of suspected communist sympathizers and foreign moles point to what is potentially the most worrisome trend in his political background: Macierewicz’s steadfast belief in his own correctness in locating traitors and his refusal to reach compromise with those he has so identified. As a revolutionary, these qualities helped to keep Macierewicz struggling when all hope seemed to be lost. As a politician, they have made Macierewicz a divisive figure who has been at the center of the toppling of one government and is now focal to attacks on the current government. It is surely only a matter of time before Macierewicz is again embroiled in controversy as he continues to enunciate views, which both appeal to and repel significant portions of the Polish electorate as it grapples with diverse political and ideological legacies of communist rule. In a country that appears increasingly divided into two opposing camps, Macierewicz personifies –and exacerbates- the differences between them and their visions for the Polish future.Dr Siobhan Doucette is an independent scholar whose research focuses on the Polish democratic opposition. She is currently completing her first book on the Polish independent press in the 1970s and 1980s. She lives in Jamaica.

![Macierewicz with Jacek Kuroń. [Source: Gazeta Wyborcza]](https://notesfrompoland.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/z15504117vw-komitecie-obrony-robotnikow-jacek-kuron-blisko-w.jpg?w=300&h=218)

![Macierewicz in 2015. [Source: polskieradio].](https://notesfrompoland.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/b2428b44-9915-4de5-8212-88d667cbf7e8.jpg?w=300&h=165)

You write about his belief of correctness in “locating traitors and his refusal to reach compromise with those he has so identified”. Meaning that he should cooperate with the ones he identified as traitors? Mr Macierewicz is one of the most morally strong people I’ve ever met and he does what others only talk about. Everybody knows that Poland is a playground for Belarusian and Russian spies and nobody does anything about it. He, on the other hand, has proved to be strong enough to walk into their nest (NATO building) and kick them out. They even had the Russian FSB logo on their wall, while the Polish eagle was hidden behind a curtain.

Majority of Polish people have opinion that Macierowicz is rusian agent or what is worse is a person with mental disorder. At first he destoyed polish inteligence, and mow he is destroing polish military officers.